Unlike the

English alphabet which includes 26 letters, the Chinese work with radicals,

which are the basic forms to create a character. Knowing the radicals is like

knowing the letters to create a word. Once you know the radicals, you can go on

to create many combinations to form different characters. After doing a quick online

search, there are 214 radicals. Don’t feel overwhelmed. It’s not as hard when

you start recognizing them. If you want to read Chinese, you have to be able to

recognize the radicals because the majority of the Chinese characters did not

derive from pictograms as many believe, but from phono-semantic compounds where

the radical tells you the general meaning of the character and then you base

your pronunciation based on the rest of the character. Even if you couldn’t

understand the character, you can at least get a hint from the general meaning

of the radical. You may not memorize all radicals, but you need to at least

recognize them. Some radicals are very common while others are not. If you are

an overachiever and want to understand it fully, I recommend recognizing

traditional radicals first and then moving on to simplified radicals because

then you can often see the process of how a traditional radical became

simplified.

Before we

move on, I want to clarify that the Chinese writing system does not have

letters. I’ve heard people call Chinese characters “letters” all too often and

it drives me mentally crazy. Please refer to Chinese characters properly as

“characters” and not as “letters.” Characters have the potential to become a

word by itself while letters cannot. There were people who come to me and ask

me how I would “spell” a character. We

do not “spell” characters, we “write” characters in Chinese. By the way, I have

been a hypocrite and used the wrong terminology before, but I do make effort to

correct this misconception. We all make mistakes.

In this

post, I’ll teach you the most important skill you will need for reading

Chinese: HOW TO LOOK UP A CHARACTER IN A CHINESE DICTIONARY. While I don’t have

any experience looking up words in a simplified characters dictionary, I

believe it uses the same method as the traditional characters dictionary.

I know that

there’s a bunch of English to Chinese dictionaries online, but there will be

instances where I can’t find a word and I have to resort to using the stroke

count method to find a word in the dictionary. I have yet to find an online

dictionary that is fully complete with every single English word so chances

are, you will need to resort to the stroke count method at some point. Even if

you use the pinyin method, which is the most popular method of romanization for

Chinese pronunciation, you might not be so sure what sounds you are hearing. What’s

great about online dictionaries is that all you have to do is click on links to

get to the character you are looking for. When I was young, I had an actual

dictionary and I had to find the page with the correct stroke count of the

radical first, find the section the radical was in, and then find the character

by the total stroke count. It was a lot of work and frustrating. Even so, a

Chinese dictionary is fun to have if you want to spend the money and time. You

can brag to all your friends who will be amazed how you can figure it out or

they may call you stupid for not figure it out online instead.

How do we

figure out how to look up a word? As I mentioned before, you use the stroke count method. Interestingly, when

I researched this topic on Wikipedia, I found that people from Hong Kong or

Macau use the stroke method as an IME (Input Method Editor) to type on their

mobile phones where one key is one type of stroke. Cool!

Stroke count

is written or typed 笔画 and in pinyin

romanization, bǐ huà. As

aforementioned, pinyin is reserved for romanization in Mandarin. I’ll explain

more about pinyin in the future.

I definitely

learned stoke marks as a child in Chinese elementary school, but I have long

since forgotten the formal lessons. According to Wikipedia, we have six basic

strokes and four combination strokes. Before I get to that part, let’s define a

stroke. After searching the word “stroke” in the dictionary, I became

overwhelmed at all the many meanings it had. I think this Merriam-Webster

definition is the best official definition I can find:

12a : a mark or dash

made by a single movement of an implement

Well, I’d

like you to think of it simply as a mark

you make from the time you place your pen or brush down on paper to the time

you lift up your pen or brush from the paper. This is assuming that most

people write on paper with a pen or less commonly, a brush (for calligraphy.)

There are, of course, other ways to write besides with a pen or brush such as

in romantic scenes where a guy would write on the sand with a stick at a beach

to profess his love or when a jailbird tries to scratch a message on a wall

with a rock or something, but we’re not going to focus on the alternatives,

which is why the Merriam-Webster’s use of the word “implement” in the

definition is appropriate and my definition is too narrow. When I was in

Chinese elementary school, it was a common practice to mentally envision what I

was writing by writing the characters with my finger either in mid-air or on my

desk. You should try it too. When I didn’t remember how to write a word, I

stuck out my hand, palm up, and my mom would write the character on my hand

with her finger. It’s a complicated form of sign language.

To recap, as

soon as you lift your pen or brush up from the paper, the stroke ends. Think

about how many strokes it takes to create a character. My maiden surname “龔”

(Gong1) has twenty-two strokes. My Chinese teacher always uses my surname as an

example for the class to demonstrate strokes because it’s one of the most

difficult surnames if not, the most difficult surname to write.

One

important rule to note about writing strokes is that you always start from the

top left and end at bottom right. There are exceptions, of course, but you

can’t go wrong if you stick to my basic rule of top left to bottom right.

According to Wikipedia, there are eight basic

rules of stroke order in writing a Chinese character:

- Horizontal strokes are written before vertical

ones.

- Left-falling strokes are written before

right-falling ones.

- Characters are written from top to bottom.

- Characters are written from left to right.

- If a character is framed from above, the frame is

written first.

- If a character is framed from below, the frame is

written last.

- Frames are closed last.

- In a symmetrical character, the middle is drawn

first, then the sides.

BASIC STROKES:

Dot (、)

Diǎn, 點/点

"Dot" Tiny Dash, Speck

Dots look similar to commas. Even in the word for “dot”

which is “diǎn,” you see there are four dots on the bottom (the left

character 點 is the traditional character

for diǎn and the right character 点 is

the simplified character for diǎn. In Cantonese, 點 is pronounced "dim2." A diǎn is written just like a backwards comma in a rightward

direction with a slight hook to the left as you see in the picture. You should

always write the diǎn from top left to bottom right and then hook it slightly.

I usually don’t do the hook when I’m writing, but you should do it if you’re

practicing calligraphy. Based on the information you know already, do you write

the four Diǎns first or last in the simplified character for 点?

(Answer: Last as they are located at the bottom!)

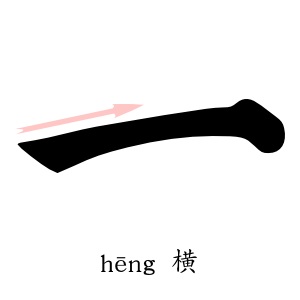

Horizontal (一)

Héng, 横

"Horizontal" Rightward Stroke

This horizontal stroke looks

just like an em dash or just a line across. The word for a horizontal stroke is

“héng.” or in Cantonese, "waang4." I think it’s only natural that we would be inclined to write the héng

stroke from left to right so I don’t need to explain this one too much. If you

take only the left-hand tree radical "木" from the character 横, at which point do you

think you would write a héng stroke?

(Answer: First. Not only is

it located near the top, but horizontal strokes are written before vertical

strokes.)

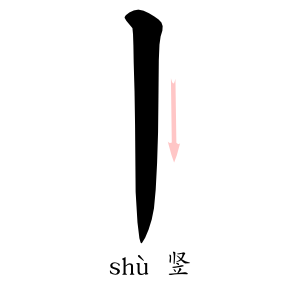

Vertical (丨)

Shù, 豎/竖

"Vertical" Downward Stroke

The vertical stroke, shù or syu6 in Cantonese, looks

like a pipe or the number one. Naturally, we write it from top to bottom. It

looks like the shù character 竖 is

more harder to write than the actual stroke itself. The actual character 竖 has shù strokes located at

the top left. Do you think we write them first or last?

(Answer: First, since the shù

strokes are located at the top left. We usually write from the top left.)

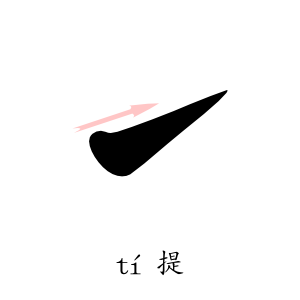

Rise( ‘ )

Tí, 提

"Rise" Flick Up and Rightwards

The "rise" or tí is a stroke going in a upper-right

direction. The reason why the bottom of the stroke is thicker is because when

you are using a brush, the brush naturally stays longer in the initial spot

than at the end of the stoke where you lift up your hand while keeping your

wrist in place and the brush lifts away from the paper. When using a pen or

pencil, a simple stroke to the upper right will suffice. As usual, the stroke is written from left to

upper right. 提 is pronounced "tai4" in Cantonese. The shou3 or “hand” 扌 radical is located on the left hand

side of the word 提.

This may be a trick question, but can you tell me when you would write the tí stroke in the

扌 radical?

(Answer: It is the

fourth and last stroke. It is one of the exceptions to the stroke order rule.

At least we finish it up on the right side! That could be considered the bottom

right. By the way, the bottom of the 扌character is a hook or gōu stroke, which we haven’t covered yet.)

Right-falling (丶)

Nà, 捺

"Press Down" Falling Rightwards (fattening at

the bottom)

Nà, 捺

"Press Down" Falling Rightwards (fattening at

the bottom)

The nà (or naat6 in Cantonese) stroke

is always written from top left to bottom right. The reason why the bottom of

the stroke is thicker is because the brush stays longer on the paper at the end

of the stroke since your brush is closer to your body than when you first

started. This stroke is often used last when writing a character since you

would end up in the bottom right. From what I see, the word 捺 itself has two nà

strokes. If you break down just the right hand side of the character "奈" from 捺 into a top half 大 and

bottom half 示, at which stroke would you write the nà?

(Answer: The nà stroke is the last stroke each time. As

mentioned before, usually the nà stroke is used as the last stroke since we usually end

up at the bottom right.

Left-falling (丿)

Piě, 撇

"Throw Away" Falling Leftwards (with a slight

curve)

Lastly, we cover the piě (or pit3 in Cantonese)

stroke. This stroke is a little tricky since we actually start from

the top-right and end up at the bottom left. Doesn’t this go against all

rules? We already run into one exception

in stroke writing. You would write this the opposite way of the previously

covered tí stroke, only steeper in the

degree angle. There are three piě strokes in the character 撇, but to make it easier, let’s focus on the right side

radical of the character, 攵 (pu1.) At which point would you write

a piě stroke?

(Answer: First. It

is located at the top left. Yay, at least we’re following rule orders again. If

you were studying, you’d see there is another piě stroke. The third stroke is a piě stroke after the héng stroke.)

COMBINATION

STROKES:

When you mastered

all the basic strokes, we can go into combination strokes. Combination strokes

require a basic stroke and at least one combination stroke. Remember, all these

strokes are done in one stroke without lifting your pen or brush. A full list

of possible combinations is found in a chart located at Wikipedia:

Zhe: ( 90° angle)

Indicates a change in stroke direction, usually 90° turn, going down or going

right only.

You cannot actually write the zhé (or zit3 in Cantonese) stroke by itself because it depends on the direction of the last

stroke you are writing. If you were writing a héng stroke, then your zhé stroke

would always go 90° downwards. It

is like writing a horizontal line followed by a vertical line downwards in one

stroke. Remember, we usually write from top to bottom. If you were writing a shù stroke, your zhé stroke would always go 90° to the right. To recap again, we usually write from left to right. If we were

to add another Zhé as in Shù Zhé Zhé, we would make something like a

staircase. Are there any zhé strokes in the word, 折?

(Answer: No. Surprising,

huh?)

Hook: (亅, 乛)

Gōu, 鉤/钩

"Hook"

Appended to other strokes, suddenly going

down or going left only.

Just as it looks, the hook makes a type of check mark

shape and ends quickly with a flick of a pen or brush. Depending on the last

stroke you made, the hook can go upwards-left or downwards-left, but never to

the right side. The gōu (or ngau1 in Cantonese) stroke is best understood when in combination

with other strokes since it cannot be by itself. There are five types of gōu

strokes: Hénggōu, Shùgōu, Wāngōu (乚), Xiégōu, and Pinggou.

In the character 鉤, let’s break down the

character to just the right side: 句. This may be an advanced question, but when would

you write the gōu stroke?

(Answer: At the

end of the second stroke after you complete the héngzhé stroke. This

second stroke becomes the héngzhégōu stroke since you never lifted up your pen

or brush.)

Let’s be more

ambitious with the character, 句. Why do

you think the héngzhégōu stroke is not written last? Doesn’t the stroke end up

at the bottom right? It is because characters are written from top-left to bottom-right.

The piě stroke is obviously the first stroke followed by the héngzhégōu stroke,

which begins right next to it even if it ends below the 口 next to it. This question might be tricky, but can

you finish off the 口to complete the character 句?

If you use rule number four (characters are written

from left to right) followed by rule number three (characters are written from

top to bottom), the answer would be: a shù stroke, back to the starting point to make a héngzhé stroke, and then a héng stroke to

close it off the bottom (using rule number seven: frames are closed last.) The

kou3 口 character is the

actual character for “mouth” and this character is the basis for the creation

of “frames.” Kou3 does not have to be completely closed where one of the four

sides is missing and that is what we mean be framing. I’m probably going a

little too far with this topic since we’re supposed to concentrate on

combination strokes right now.

You should already have the knowledge to

write hénggōu and shùgōu. Try to write them!

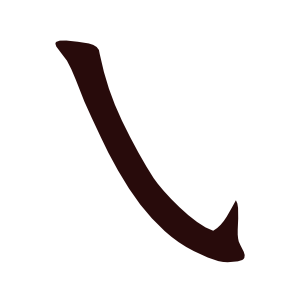

Bend: ( ) )

Wān, 彎/弯

"Bend"

A tapering thinning curve, usually

concave left (convex outward right.)

The wān (or waan1 in Cantonese) stroke is

a bend. I’ve seen on an online forum where a person asked about the difference

between a wān stroke and a piě stroke. My opinion is that when you are writing

a piě stroke, you naturally make a slant, but not enough to make it a bend. To

me, writing a piě stroke is like writing a line-like comma on paper. The wān

stroke, however, does have a circular appearance. I think of it as an English

right-sided parenthesis ")" punctuation mark. As previously mentioned in the gōu section, the wān stroke is usually

written in combination with the gōu stroke. I think it’s

easier if we saw some examples: 乚,

乙, etc.

I do want to mention another type of wān stroke that is horizontal. The

horizontal wān stroke is called a ping1 stroke or a biǎn stroke. Ping means “leveled” in English and Bian means "flat." The ping stroke is

written from left to right and typically followed by a gōu stroke. The perfect example of a ping

gōu stroke is the character for heart: 心

Does the character 彎 have a wān stroke?

(Answer: Surprisingly, no. The last stroke at the bottom of

the wān character is

considered a shùzhézhégōu

stroke.)

Slant: ((,)

Xié, 斜

"Slant"

Curved line, usually concave right

(convex outward left).

The xié (or ce4 in Cantonese) stroke is a

right or left slanted stroke which is usually combined with a gōu stroke at the

end. As usual, you start from top and end at the bottom. It is different than the nà or piě

stroke in that the slant is almost straight in the beginning or very steep and

then curves as you move toward the bottom. It is like drawing a side of a tree

trunk. You would write a slanted shù stroke towards the direction you are going

(either left or right), but as you reach the bottom the curve intensifies.

Think of a rollercoaster as we go from a high point into a drop. Does the character 斜 have a xié

stroke?

(Answer: No. One

would think it should have one, but surprisingly, it doesn’t.

You may

notice some of the strokes may look the same when writing them, but keep in

mind that the strokes are based on calligraphy writing and not regular

pen/pencil writing. Many fine details such as thickness of a stroke are left

out when writing with a pen or pencil. If you understand and practice your

strokes, writing a Chinese character will be easier than before.

The great

part about knowing stroke order is that you can also successfully write Korean

and Japanese the same way, from top left to bottom right as the rules are

basically the same with some exceptions. No matter how complicated a character

is, it still takes up the same amount of space so when you write, be careful to

keep the characters about the same “block” size. Having a Chinese or an Asian

type of workbook can help you practice writing characters.

If you are

interested in typing by using the stroke method, you should take a look at the Wubihua Chinese input method that is very popular for cellphones. The Wubihua method only uses the numerical

keypad. The numbers 1-5 are used:

#1 – Héng or Tí Stroke

#2 – Shù Stroke

#3 – Piě Stroke

#4 – Diǎn or Nà strokes

#5 – Compound and other strokes

I have yet to find a program for Wubihua though.

I think we

covered everything regarding strokes.

Check out this website which recaps all the strokes I covered:

When you are more familiar with the

strokes, let’s move on to radicals in my next post!