Ever since I went to the Terracotta Warrior exhibit in Times

Square, I wanted to know more about the history of China. To be honest, I have

never been interested in China’s history because it’s such a long time period

and hard to understand, but now, I am starting to appreciate the Qin dynasty’s

interesting story. Before you can say how boring this subject is, I assure you,

it’s not as boring as you would think. I will try to keep it as easy to

understand and interesting as much as possible.

I would like to thank the Terracotta Warrior exhibit,

Cantonese Sheik Dictionary, and Wikipedia for all the factual information on this blog.

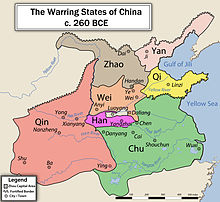

Let’s start at the pre-Qin Dynasty period: The Warring

States period.

|

| Credit: wikimedia.org |

During the Warring States Period (戰國時代 zin3 gwok3 si4

doi6 in Cantonese/ 战国时代 4 2 2 4 in Mandarin or

alternatively known as 戰國七雄 zin3 gwok3 cat1 hung4 in Cantonese or 战国七雄 4212 in Mandarin to have a similar meaning like “The

Mighty Seven Warring States”) happened at arguably around 475 B.C. There were

seven states that ruled the land of China, each refusing to succumb to the

other states. The seven states are usually listed in the following order:

Qin – Western state- 秦 ceon4 (C) 2 (M)

Qi – Mid-Eastern State- 齊 cai4 (C) 齐 2 (M)

Chu – Southern State- 楚 co2 (C) 3 (M)

Yan – North-Eastern State- 燕 yin1 (C) yan1 (M)

Han – Mid-South State- 韓 hon4 (C ) 韩 2 (M)

Zhao – Mid-Northern State- 趙 ziu6 (C) 赵 4 (M)

Wei – Middle state- 魏 ngai6 (C) 4

The ruler of these states acted like kings, but not at the level where

they believe they were the “mandate of heaven” as in acting based on the gods’

directions or heaven’s orders as the Zhou emperors had claimed before them.

What fascinated me about the seven states is that they each had their

own type of currency. One type of currency can be clearly seen in one scene of

the movie, “Hero” when the character “Nameless” (Jet Li) drops some currency

into the blind old man’s dish before fighting “Long Sky” (Donnie Yen). Can you imagine carrying currency that looks

like a long meat cleaver? Or how about imagining your favorite wuxia

hero strolling down the streets carrying bulky Qi “broad-swords” currency?

|

| Warring States Currency |

|

| Warring States Period Currency |

Basically, the Qin state conquered all the other states one by one with

Han State in 230 B.C., located directly east, being the first to surrender and

Qi being the last to surrender in 221 B.C.. It was like the Qin empire went

bowling and knocked down the other states over a span of many years.

|

| Credit: www.chinaknowledge.org |

In 230 B.C., the Qin state conquered the Han state based on fear. The

Qin state attacked the Zhao state, leading King An of Han to think that the Han

state would be the next target. King An of Han quickly sent diplomats to

surrender his kingdom without a fight to prevent further bloodshed.

In 225 B.C., The Qin state conquered the Wei state. The Wei state was

fortified with strong walls so the Qin state decided to use the Yellow River to

flood the city. King Jia of Wei was forced to leave the city and surrender to

the Qin army in order to save his people.

In 223 B.C., the Chu state fell, but not without a good fight.

Initially, the Qin attack was led by an inexperienced general named Li Xin. The

Chu forces, familiar with their own territory, was able to drive the Qin forces

back and burned down two of Qin’s large camps. The Chu forces then waited

confidently for Qin’s second invasion, but after a year, it seemed as though the

Qin army was reluctant to attack. The Chu army made the grave mistake of

disbanding during what they thought was a time of peace. The Qin quickly seized

the moment and attacked with full force. Up to a million soldiers participated

in this battle, which was significantly larger than the previous Qin battle

with Zhou. The Chu kept fighting using guerrilla-style tactics until their

leader, Lord Changping of Chu, died.

In 222 B.C., the Zhao state was conquered by Qin followed

by the Yan state. After the news of Zhao’s downfall, Crown Prince Dan of Yan

sent an assassin named Jing Ke to assassinate the king of Qin. After Jing Ke

failed, the king of Qin, became enraged

and ordered more troops to over to the Yan state, which was ultimately

conquered.

Finally in 221 B.C., the last state, Qi, was conquered. The Qi state

did not assist the other states in the battle against the Qin state. When the

Qi state heard that the Qin army was coming to invade the Qi state, the Qi

state quickly surrendered, signifying the end of the Warring States Period and

the unification of China under the Qin dynasty.

Why was the Qin state so powerful? The Qin army was huge and led by

ruthless generals. The Qin generals disregarded all former “war etiquette” and

did not fight honorably. For example, waiting for the enemy to cross a river

and gathering their forces afterwards like Duke Xiang of Song did for the Chu

army before starting a fair fight is out of the question. (By the way, Duke

Xiang lost the fight.) If the enemy had a weakness, the Qin army used it to

their advantage. The Qin employed qualified men from other states and the army

itself did not suffer from internal struggles.

For each state that was conquered, the Qin empire was ruthless. King

Zheng, the king of Qin, ordered all weapons to be confiscated and melted

down. All scholarly books were burned

and scholars killed. King Zheng eliminated the possibilities of further

uprisings and rebellions against him.

While the Qin state was very powerful, they were seen as savage. On the

Wikipedia website, a nobleman from the state of Wei criticized the Qin state as

"avaricious, perverse, eager for profit, and without sincerity. It knows

nothing about etiquette, proper relationships, and virtuous conduct, and if

there be an opportunity for material gain, it will disregard its relatives as

if they were animals."

In 221 B.C., after all of what seems to be China at the time was

conquered with all the other states defeated, the king of Qin, 秦王(ceon4 wong4 in Cantonese, 2 2 in Mandarin), changed

his title from his given name 赵正/趙正 (Ziu6 Zing3 in Cantonese, Zhào Zhèng in Mandarin) to Qin

Shihuang 秦始皇, the shortened title, or by his more formal title 秦始皇帝(ceon4 ci2 wong4 dai3 in Cantonese, Qín Shǐ Huángdì in Mandarin), meaning

the “first emperor of China.”

Previously, in the Zhou dynasty in 1045 B.C., a ruler called

himself “王” (wong4

in Cantonese, 2 in

Mandarin), which took the meaning of “big man” at the time. Later on,

the word 王 was adapted to mean “king” of “chief.” So, 秦王 would mean “Qin Ruler” or “King of Qin” or “Qin King.”

After

the King of Qin conquered all of China, he discussed his appropriate title with

his ministers. The ministers suggested the title, “Tai Huang” 太皇 (taai3 wong4 in Cantonese, tai4 huang2 in Mandarin), but the king believed

he embodied the virtues and achievements of the 三皇五帝 (saam1 wong4 ng5 dai3 in

Cantonese, sān huáng wǔ dì in Mandarin) Three Monarchs and Five Emperors. Therefore, the king of Qin

removed the characters Tai 太and added Di 帝 to create Huang Di 皇帝. Since he was the first emperor, he called himself “Shi,” meaning

“the first” His full title then became 秦始皇帝.

In the title, 秦始皇帝:

始 means “first” of the “start.” The emperor’s heirs would be then titled “Second Emperor,” “Third Emperor,” etc.

皇帝 means “emperor” if you put the two characters together. If you break the characters apart, it means something like “royal surpreme-ruler.” Scary, huh? In ancient times, hearing the term may make our body tremble. In this modern time period, this term is not that scary. In fact, this is a term you would use to refer to a lazy person who makes a lot of demands. At least in Cantonese, a parent would probably refer to her child as a “couch potato” son or daughter, 皇帝仔/皇帝女 (wong4 dai3 zai2 in Cantonese, huang2 di425 in Mandarin / wong4 dai3 neoi5 in Cantonese, huang2 di4 32 in Mandarin).

The Qin dynasty lasted from 221 B.C. to 207 B.C. Future dynasties,

especially the next dynasty, the Han dynasty, retained many Qin dynasty

structural elements during their rule. In fact, the Romanized name of the

Chinese country, China, is derived from the Qin dynasty based on European

knowledge at the time.

In part two, I will explain more about the life of China’s famous

ruler, 秦始皇. Qín Shǐ Huáng was a strong ruler, yet he had his dark

sides. Be sure to check out the next part!